I've been indulging in a bit of Brönte lately. I recently re-watched Jane Eyre (BBC 2006) and I just finished reading Agnes Grey.

I'm intrigued by the regular recurrence of heartless beauties in both Charlotte and Anne's works. Clearly, beauty is a big deal for the Brontes. But not in a good way.

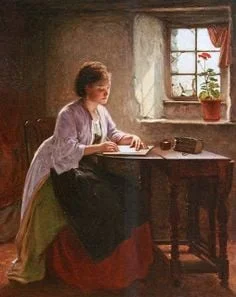

The beautiful Blanche Ingram (with plain Jane in the shadows).

There's a distinct similarity in Agnes Grey, Jane Eyre, and Villette in which the first-person narrator feels largely invisible as a quiet, thinking person and as a plain-looking female. Of course, in all these stories, there is often also a consideration of class wherein the narrator's social position is one of diminished importance compared to those around her.

Is this a peculiar feeling to the Bronte sisters, who were obviously brilliant intellects and astute observers? Or is it a common burden for any girl of the era who has more intelligence than good looks? Do the beautiful girls get all the attention?

Well, not always of course. Rochester chooses Jane over Blanche.

Good choice, Rochester.

Conversely, perhaps it is actually something of a curse to be born beautiful as a girl in that era. Is there really an inverse relation of brains to beauty, or are beautiful girls taught early on to consider their self-worth as largely pertaining to appearance? Do they steadily grow into all-consuming vanity after years of being raised to give inordinate attention to the outside package?

Agnes Grey confesses that "it is foolish to wish for beauty. Sensible people never either desire it for themselves, or care about it in others. If the mind be but well cultivated, and the heart well disposed, no one ever cares for the the exterior. So said the teachers of our childhood; and so say we to the children of the present day. All very judicious and proper, no doubt; but are such assertions supported by actual experience?"

It feels like Agnes is trying to use good sense and logical reasoning to quell a longing for a little more beauty. Her musing on beauty comes at a time when she discovers that the dazzling Miss Murray intends, merely as a vain game, to attract the attention of the man Agnes loves. The plain-looking Agnes Grey acknowledges that "we are naturally disposed to love what gives us pleasure, and what more pleasing than a beautiful face...?"

Poor Agnes is in anguish over the thought of being passed over simply because she lacks the power to make herself known; a gift or benefit naturally accorded to those that are beautiful. If a woman "is plain and good ... no one ever knows of her goodness, except her immediate connections." Whereas, those who are favored by nature to be beautiful may have "an angel form [which] conceals a vicious heart."

Miss Murray does seem to have something of a vicious heart. In toying with the affections of one her four suitors, she finds his heartfelt marriage proposal an amusing incident to relay to others -- even after the suitor begs her to keep his failed overture a secret. She has little or no concern for others.

In Villette there is a Miss Fanshawe who enjoys keeping two or more men dangling after her. And one of them is admired by the plain-looking narrator, Lucy Snowe. Again, the beautiful Miss Fanshawe is portrayed as having little consideration of others' feelings. The world exists to amuse and venerate her.

The belle of the county in Jane Eyre, however, seems merely ambitious, not vicious. Blanche Ingram is interested in becoming mistress of Thornfield. Her beauty enhances her prospects, so custom assumes, in realizing her goal. But Rochester discerns that she is incapable of loving anyone. Such beauties like Blanche seem to truly lack the ability to put another person's happiness above their own.

The inability to care for others reminds me of someone else at her most vicious. (Fanny Watson - BBC 2004)

Where does all this vanity and indifference to others come from? Does being born with good looks naturally create a heartless, narcissistic female?

Social conditioning has a great deal to do with creating these hollow shells. Parental expectations and values are often transferred to their offspring. Parents guide their children's minds into channels of thought either conducive to or wholly opposed to worthy pursuits that enrich character, such as self-improvement, and respect for others.

There is a recurring theme in Agnes Grey that reveals how children are turned into selfish, undisciplined brats by their parents' own inflated sense of self-importance, based on the shallow markers of wealth, class, or physical appearance.

I loved the particularly candid observation made in a conversation between Agnes and her love-interest:

"... some people think rank and wealth the chief good; and, if they can secure that for their children, they think they have done their duty."

"True: but is it not strange that persons of experience, who have been married themselves, should judge so falsely?"

With such empty values being transmitted to children, it is hardly surprising to see the pretty Miss Murray get her just deserts. Having been taught to seek grandeur and wealth her entire life, she achieves her goal in marrying a titled man with impressive property. After a glamorous honeymoon through the capitals of Europe, she becomes perfectly miserable within a year -- tied to a man she detests, and living with an overbearing mother-in-law.

Taking such lackluster results into consideration, the highest advantage may ultimately belong to the plain girls, who have to rely on something other than beauty to bolster their identity and self-worth. It's the quiet girls in the shadows, after all, who have much more opportunity to observe and reflect and grow a heart while others earn society's attention.

What should a girl aspire to be? A thinker (and lover!) or a showpiece?